Old figures, old rules, old scenery, old articles, old reviews, and old wargamers. Not old school. Just old.

Wednesday, 30 December 2009

Wednesday, 23 December 2009

The French Invasion of England in 1810, Part 4, by Harold Gerry

(A campaign game played by the Mid-Herts Group; for strategic rules see June "Newsletter").

The West Country, May 9th-14th. At Taunton, on the afternoon of the 9th, the French had just begun to take possession of the captured town when their cavalry, scouting along the Bristol road, reported a new English force entrenched just across the River Tone, blocking the road effectively. There was consternation in the French camp. The militia army driven south¬wards out of Taunton, although shaken, would recover its spirits within a day or two unless it could be relentlessly pursued. But the main English army in the West was also one day's march from Taunton, but to the westward, so such pursuit was out of the question.

The new force discovered was one of the reserve armies composed of militia, which one of the English commanders from another area had sent down into the West Country to render what assistance it could, and somehow the two commanders locally had not been informed. So the Taunton general had fought and lost his battle without realising that this second English force (about 4 regiments) was only about 2 hours' march away. (The player originally dealing with the West Country had had to hand over, for business reasons, to temporary assistants at this stage of the campaign, and a most realistic "fog of war" descended on all this area as a result).

At length the French decided that a trap was closing in on them, and marched north-west along the road to the Bristol Channel. The main English army tried to cut them off by marching over secondary roads, but, having force-marched the day before as well, had at length to give up and call a day's rest.

The French thus escaped, but the British profited from the halt to re-group. Some units went back towards Salisbury, as London was still anxious about Portsmouth, which area was not too strongly guarded. A force of about 16,000 of all arms (1 figure = about 50 men) hurried after the French, who were now covering a temporary base at Minehead.

Unknown to the British, the local French commander had just sent word to Paris that he was retiring on Launceston and Falmouth (both now fortified) and that there was now no hope of breaking through up to the Severn Valley to raise the Midlands as originally planned. The British were still obsessed with the possible danger to the Plymouth base (the initial French landings at Falmouth and Lyme Regis were intended to confirm the British in this fear, to draw the British westwards whilst the main French thrusts went into the Midlands from West and East).

So in fact the Western stage of the campaign was now almost over. Nothing further of significance would take place. The French used any available shipping to ferry troops over to Wales, which they had suddenly realised must have been very denuded of troops in order to reinforce the fighting in Somerset. But the British, naturally, knew nothing of all this as yet, and could not withdraw too many units from the West Country in case the next major landing of French reinforcements was to take place near Plymouth. The base must be held at all costs.

To cover their embarkation, the French with about 8,000 men, stood to fight along the line of the small river and woods at Dunster, in North Somerset. Nearly two hours of daylight were left. (It was established by dice throw that the English forces had overtaken the French, and further dice fixed the number of game-moves possible before dark).

The French units were mostly concealed from view, (and therefore not laid down on the wargame table), the terrain being very broken, with many woods. The English commander was forced to attack "blind", and this possibly led him to direct his thrusts mainly at the area between village and sea, where he could at least expect no very complicated surprises. He could have attacked more recklessly had he known that about a quarter of the French army were at Minehead bay embarking on shipping to cross to Wales to re-open the campaign there. The French at Dunster were outnumbered nearly 2 to 1.

The English left was intended merely to contain any French opposite them. In the centre, four militia regiments moved directly on the bridge and village, with instructions to attack repeatedly and regardless of losses, whilst all the cavalry and the best regular infantry tried to envelop the French line from the sea side. The militia ran into the expected skirmishers' fire from the woods on the East bank, but one unit sufficed to deal with this, whilst the others advanced determinedly. But each regiment as it approached into grape range and long musket range lost over a quarter of its strength to the concentrated fire from the houses and barricades opposite. The attack came to a stop, two of the regiments routing. But the defenders realised their luck would not hold much longer. A rifle militia regiment had just cleared the hedged field area downstream, and was moving up the river to engage the batteries and muskets from the more advantageous rifle range (12" as compared with 6" for muskets).

On the English right, the flanking force had just crossed the small river, in some disorder, when they were charged at a nicely judged moment by a cuirassier regiment. The leading English cavalry unit routed, and carried with it the second, which was in the river. "Never mind, the Guards will stop the rot", opined the C. in C., that unit being next to have its morale tested. To his disgust they broke also, and the entire column of seven regiments was pushed back from the river, due to the narrow frontage. (The Guards threw four morale dice, needing a 5 or 6 on one at least; they threw 4, 2, 2, 1). By the time the unshaken rear units could move up to the river, it was too late to re-mount the attack.

Then the somewhat incompetent English commander found he had scored a partial success after all, but with the part of his force of which he had expected nothing. His left wing had simply plodded forward warily to the river, their cannon preventing the French guns opposite from doing the same execution which had happened at Dunster town. The French, afraid of losing the batteries which had been their main battle-winning asset so far in the campaign, limbered up and escaped out of range, and English light companies supported by an infantry brigade in line took the hills where the main road south to Exeter left the Dunster area. Unknown to anyone on the English side, this was to have been the French route back to their smaller supporting forces in Devon and Cornwall. So when they retired next morning, before dawn, the French had to take the long route through Minehead and Barnstaple.

The English Western army followed slowly, to within a few miles of Launceston, disposing a screen of troops about the north and east sides of the town by the even¬ing of the 14th. At about this time bad news from Wales began to arrive, and some of the Welsh militia regiments were marched off to the Bristol Channel to reinforce tie small forces in South Wales, where the next decisive part of the campaign was going to take place.

TO BE CONTINUED

I regret the map accompanying this article of the Battle of Dunster is so faint I can not reproduce it here.

This article appeared in Wargamer's Newsletter #102, in September 1970.

The West Country, May 9th-14th. At Taunton, on the afternoon of the 9th, the French had just begun to take possession of the captured town when their cavalry, scouting along the Bristol road, reported a new English force entrenched just across the River Tone, blocking the road effectively. There was consternation in the French camp. The militia army driven south¬wards out of Taunton, although shaken, would recover its spirits within a day or two unless it could be relentlessly pursued. But the main English army in the West was also one day's march from Taunton, but to the westward, so such pursuit was out of the question.

The new force discovered was one of the reserve armies composed of militia, which one of the English commanders from another area had sent down into the West Country to render what assistance it could, and somehow the two commanders locally had not been informed. So the Taunton general had fought and lost his battle without realising that this second English force (about 4 regiments) was only about 2 hours' march away. (The player originally dealing with the West Country had had to hand over, for business reasons, to temporary assistants at this stage of the campaign, and a most realistic "fog of war" descended on all this area as a result).

At length the French decided that a trap was closing in on them, and marched north-west along the road to the Bristol Channel. The main English army tried to cut them off by marching over secondary roads, but, having force-marched the day before as well, had at length to give up and call a day's rest.

The French thus escaped, but the British profited from the halt to re-group. Some units went back towards Salisbury, as London was still anxious about Portsmouth, which area was not too strongly guarded. A force of about 16,000 of all arms (1 figure = about 50 men) hurried after the French, who were now covering a temporary base at Minehead.

Unknown to the British, the local French commander had just sent word to Paris that he was retiring on Launceston and Falmouth (both now fortified) and that there was now no hope of breaking through up to the Severn Valley to raise the Midlands as originally planned. The British were still obsessed with the possible danger to the Plymouth base (the initial French landings at Falmouth and Lyme Regis were intended to confirm the British in this fear, to draw the British westwards whilst the main French thrusts went into the Midlands from West and East).

So in fact the Western stage of the campaign was now almost over. Nothing further of significance would take place. The French used any available shipping to ferry troops over to Wales, which they had suddenly realised must have been very denuded of troops in order to reinforce the fighting in Somerset. But the British, naturally, knew nothing of all this as yet, and could not withdraw too many units from the West Country in case the next major landing of French reinforcements was to take place near Plymouth. The base must be held at all costs.

To cover their embarkation, the French with about 8,000 men, stood to fight along the line of the small river and woods at Dunster, in North Somerset. Nearly two hours of daylight were left. (It was established by dice throw that the English forces had overtaken the French, and further dice fixed the number of game-moves possible before dark).

The French units were mostly concealed from view, (and therefore not laid down on the wargame table), the terrain being very broken, with many woods. The English commander was forced to attack "blind", and this possibly led him to direct his thrusts mainly at the area between village and sea, where he could at least expect no very complicated surprises. He could have attacked more recklessly had he known that about a quarter of the French army were at Minehead bay embarking on shipping to cross to Wales to re-open the campaign there. The French at Dunster were outnumbered nearly 2 to 1.

The English left was intended merely to contain any French opposite them. In the centre, four militia regiments moved directly on the bridge and village, with instructions to attack repeatedly and regardless of losses, whilst all the cavalry and the best regular infantry tried to envelop the French line from the sea side. The militia ran into the expected skirmishers' fire from the woods on the East bank, but one unit sufficed to deal with this, whilst the others advanced determinedly. But each regiment as it approached into grape range and long musket range lost over a quarter of its strength to the concentrated fire from the houses and barricades opposite. The attack came to a stop, two of the regiments routing. But the defenders realised their luck would not hold much longer. A rifle militia regiment had just cleared the hedged field area downstream, and was moving up the river to engage the batteries and muskets from the more advantageous rifle range (12" as compared with 6" for muskets).

On the English right, the flanking force had just crossed the small river, in some disorder, when they were charged at a nicely judged moment by a cuirassier regiment. The leading English cavalry unit routed, and carried with it the second, which was in the river. "Never mind, the Guards will stop the rot", opined the C. in C., that unit being next to have its morale tested. To his disgust they broke also, and the entire column of seven regiments was pushed back from the river, due to the narrow frontage. (The Guards threw four morale dice, needing a 5 or 6 on one at least; they threw 4, 2, 2, 1). By the time the unshaken rear units could move up to the river, it was too late to re-mount the attack.

Then the somewhat incompetent English commander found he had scored a partial success after all, but with the part of his force of which he had expected nothing. His left wing had simply plodded forward warily to the river, their cannon preventing the French guns opposite from doing the same execution which had happened at Dunster town. The French, afraid of losing the batteries which had been their main battle-winning asset so far in the campaign, limbered up and escaped out of range, and English light companies supported by an infantry brigade in line took the hills where the main road south to Exeter left the Dunster area. Unknown to anyone on the English side, this was to have been the French route back to their smaller supporting forces in Devon and Cornwall. So when they retired next morning, before dawn, the French had to take the long route through Minehead and Barnstaple.

The English Western army followed slowly, to within a few miles of Launceston, disposing a screen of troops about the north and east sides of the town by the even¬ing of the 14th. At about this time bad news from Wales began to arrive, and some of the Welsh militia regiments were marched off to the Bristol Channel to reinforce tie small forces in South Wales, where the next decisive part of the campaign was going to take place.

TO BE CONTINUED

I regret the map accompanying this article of the Battle of Dunster is so faint I can not reproduce it here.

This article appeared in Wargamer's Newsletter #102, in September 1970.

Tuesday, 15 December 2009

Monday, 7 December 2009

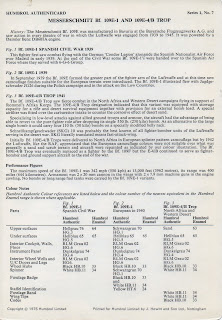

Humbrol Authenticards Series 1

Coming out in 1975, the first series of Authenticards covered mainly World War II aircraft and markings, along with some tanks and a couple of Great War scout aircraft. The series is reproduced in the posts below.

Labels:

Great War,

Humbrol Authenticard,

World War II

Original review of Charles Grant's "The War Game", from Wargamer's Newsletter # 116, November 1971

THE WAR GAME by Charles Grant (10" x 7½”: 191 pages; 25 photographs; 28 maps and diagrams. Published by A. and C. Black £3.00).

I had read and enjoyed most of the contents of this book when originally published in "Tradition" magazine and now this most lavish and pleasingly presented book makes re-reading it a pleasure. My enjoyment was increased because I have actually fought with Charles Grant using the figures depicted in the beautiful photographs in the book and on the same battlefield. In that connection I am very impressed with the manner in which Charles Grant remains satisfied and loyal to his rules because those given in the book are exactly the same as we used on pleasant if argumentative Saturday afternoons and Sunday mornings some eight to ten years ago. I say this with some feeling because my own rules are constantly being changed or amended as some new situation arises that causes dissatisfaction.

It is a most pleasingly presented book presumably aimed at the beginner whom it takes in carefully explained steps through the mechanics of fighting that neglected but fascinating and colourful warfare of the mid-l8th century. Charles backs his theories with historical illustrations and, whilst there is nothing particularly new or original in the book, it admirably does what it sets out to do - to arouse interest in a pleasing period of warfare without once straying from the fact that it is an enjoyable game that is being described and not a highly technical and intense simulation of real warfare. It may be because the wargaming careers of Charles Grant and Brigadier Peter Young have been blended together for so many years and because both fight in the same period, but "THE WAR Game" most strikingly resembles "CHARGE!" by Brigadier Peter Young and Lieutenant-Colonel J.P. Lawford in that both are exactly the same size books, both beautifully presented with gorgeous and stimulating coloured jackets, the interior lay-out, style and standard of photographs and method of presentation is remarkably similar.

The principal difference lies in the style of writing where Charles lacks the whimsicality of the Brigadier and occasionally I found irritating his over-wordy, slightly old-fashioned style of putting words together as though they were directed at youngsters. However, this may be carping because after all Charles Grant's credentials for writing such a book arise from him being an experienced veteran wargamer and not a writer.

All-in-all, this is a most pleasing contribution to the ever growing literature of wargaming and, speaking with some experience, may I say that I think that Charles's publishers have done him proud!

I had read and enjoyed most of the contents of this book when originally published in "Tradition" magazine and now this most lavish and pleasingly presented book makes re-reading it a pleasure. My enjoyment was increased because I have actually fought with Charles Grant using the figures depicted in the beautiful photographs in the book and on the same battlefield. In that connection I am very impressed with the manner in which Charles Grant remains satisfied and loyal to his rules because those given in the book are exactly the same as we used on pleasant if argumentative Saturday afternoons and Sunday mornings some eight to ten years ago. I say this with some feeling because my own rules are constantly being changed or amended as some new situation arises that causes dissatisfaction.

It is a most pleasingly presented book presumably aimed at the beginner whom it takes in carefully explained steps through the mechanics of fighting that neglected but fascinating and colourful warfare of the mid-l8th century. Charles backs his theories with historical illustrations and, whilst there is nothing particularly new or original in the book, it admirably does what it sets out to do - to arouse interest in a pleasing period of warfare without once straying from the fact that it is an enjoyable game that is being described and not a highly technical and intense simulation of real warfare. It may be because the wargaming careers of Charles Grant and Brigadier Peter Young have been blended together for so many years and because both fight in the same period, but "THE WAR Game" most strikingly resembles "CHARGE!" by Brigadier Peter Young and Lieutenant-Colonel J.P. Lawford in that both are exactly the same size books, both beautifully presented with gorgeous and stimulating coloured jackets, the interior lay-out, style and standard of photographs and method of presentation is remarkably similar.

The principal difference lies in the style of writing where Charles lacks the whimsicality of the Brigadier and occasionally I found irritating his over-wordy, slightly old-fashioned style of putting words together as though they were directed at youngsters. However, this may be carping because after all Charles Grant's credentials for writing such a book arise from him being an experienced veteran wargamer and not a writer.

All-in-all, this is a most pleasing contribution to the ever growing literature of wargaming and, speaking with some experience, may I say that I think that Charles's publishers have done him proud!

Labels:

Charles Grant,

published 1971,

Wargamer's Newsletter

Friday, 27 November 2009

Robert Louis Stevenson

Stevenson at Play, from Scribner's Magazine December 1898

I am afraid I can't remember whose blog it was I spotted this link on yesterdayto Bob Beattie's posting of this famous article about RLS and his wargaming activities.

Written by Lloyd Osbourne it incorporated a large extract from RLS's wargames campaign diary, with"mimic war correpondent" reports.

For ease of reading I am reproducing it below.

I am afraid I can't remember whose blog it was I spotted this link on yesterdayto Bob Beattie's posting of this famous article about RLS and his wargaming activities.

Written by Lloyd Osbourne it incorporated a large extract from RLS's wargames campaign diary, with"mimic war correpondent" reports.

For ease of reading I am reproducing it below.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)